Is Game Theory a good model for explaining altruism?

Is Game Theory a good model for explaining altruism?

Disclaimer

This assignment was submitted as part of my Philosophy of Mind and Language 1 seminar during my Research Master Programme at Radboud University Nijmegen, and received a final grade of 8.5/10. It has not been published by any official publishers, so here I publish it as a practice.

Introduction

In my essay, I am trying to answer the question of whether using Game Theory or specifically the Prisoner’s Dilemma is a tenable approach towards explaining altruistic behavior from an evolutionary perspective. The main motivation underlying my inquiry originates from our group project dealing with the phenomenon of cooperative breeding. While researching the topic and the connected literature, I found altruism as the most interesting of the answers evolutionary scientists offered to how and why cooperative breeding as a form of social systems evolved. This main idea got me going on a road that enabled me to get acquainted with other concepts present in evolutionary sciences, such as Game Theory, kin selection, reciprocal altruism, and many more. If not for anything else, this group project was fruitful in the sense, that I gained a more detailed insight into such ideas that were either not known or just superficially known by me.

For the main purpose of my essay, that is, to provide an answer to whether Game Theory is a feasible model to explain altruism/altruistic behavior, first I briefly explore the theory of kin selection, as I find it as the most compelling theory in evolutionary sciences for explaining the basic phenomena involved in altruistic behavior or the corresponding cost/benefit calculations each individual makes while deciding whether to engage in such activities that do not necessarily benefit - either directly or indirectly - the donor of the action. The main question, that kin selection tries to answer, is: why is it beneficial to help others, while bearing unwanted costs and risks with helping?

After presenting kin selection and the formula developed by W. D. Hamilton (1964), I turn towards possible alternative answers of helping behaviors, as I find kin selection theory lacking in the respect that it cannot decisively account for cases where the degree of relatedness between the individuals are low or zero. While kin selection is a great mathematical explanation for genetically backed cooperation, there seem to be cases that require a more refined answer, such as helping non-kin individuals.

These kinds of doubts towards kin selection were the basis of my next step towards altruism, where I found Robert Trivers and his article about the evolution of reciprocal altruism (1971). The main motivation for developing his conception is also alike to mine, Trivers found kin selection as only accounting for a narrow range of cases while lacking in explaining a wide range of other kinds of cooperative behaviors.

He presents his ideas by presenting the basic conditions for the evolution of more elaborate biological parameters, which enable the appearance of reciprocally altruistic behavior. Trivers (1971), similar to Hamilton (1964), grounds his theory on the prisoner’s dilemma, found in Game Theory, and moves on to back up his ideas by presenting some life forms that he considers showing altruistic behaviors.

Although Trivers’s (1971) theory became one of the most accepted explanations of altruism, I felt his examples somehow out of place, like he is trying to show me something by pointing to things that do not represent exactly or at most only partly, what he wants to prove. Fueled by this intuition, I found that Trivers (1971) and his theory of reciprocal altruism have been the target of criticism. Stephen I. Rothstein and Raymond Pierotti (1988) presented a reasonable critique that confirmed my suspicions about Trivers. They showed that using Game Theory as a model to explain altruistic behavior is not necessarily a viable way, as Game Theory uses a rather specific setting for cost/benefit calculations that are hardly representative of real-life situations. Instead, while presenting a framework to differentiate between the various types of cooperative and beneficent behaviors, they came up with a simpler explanation that can be applied to a wider range of situations.

This desire to find a more inclusive explanation of altruism led me to my reasons to disbelieve in the validity of a model based on the prisoner’s dilemma, but to reach this conviction I had to go through the steps presented above. Now, I turn to explain the separate steps of my journey more in detail.

Kin selection

Cooperative breeding is a concept generally used in biology, referring to such a social system where, besides an infant’s parents, other group members take part in raising an offspring. By engaging in cooperative breeding, the species in question could gain a valuable evolutionary advantage over those, not engaging in such social systems. For example, the chance of a human’s offspring to survive until maturity is almost two times larger, when compared to wild chimpanzee populations. (Kramer, 2015) This feature, combined with the relatively short birth intervals doubles surviving fertility. Mothers are facing evolutionary pressure towards meeting the needs of several offsprings from different ages, which requires varying types of time and energy investments. A natural reaction to this evolutionary pressure is to involve other helpers in the breeding process, by such coordinative activities as the division of labor.

Cooperative breeding occurs relatively rarely among animals, only in around 2-3% of species. Although it seems uncommon, cooperative breeding has evolved on several occasions across different species. The general assumption is that the help received by an infant comes approximately 50% from the mother, whereas the other 50% is provided by other kin or non-kin individuals, like fathers, grandmothers, siblings, etc.

This behavior, namely, to participate in the upbringing of an offspring from another descent, raises two evolutionary questions: (1) ‘why spend time and energy to support another’s reproductive interests?’, and (2) ‘does helping make a difference to maternal fitness and child well-being?’ (Kramer, 2015)

The main feature here is the raise of inclusive fitness either of the helper or the one receiving the help. Whether helping behavior would be favored, is dependent on the formula proposed by Hamilton (1964): rb > c. This formulation of kin selection proposes, that helping behavior will be selected towards, when rb > c is true, where r refers to the degree of relatedness, b is the raise of inclusive fitness of the recipient, and c is the cost covered by the helper. Before Hamilton, there was no tenable formulation to explain the conditions of helping behavior.

The predictions of Hamilton’s formula were supported by several studies observing species of insects, birds, and mammals, pointing to the importance kinship plays in the evolution of cooperative breeding. Three general conclusions can be made:

- the decision of whether to help is highly dependent on kinship,

- in populations where helping kin are more preferred, helpers have more influence on the recipients,

- the degree of discrimination among kin increases with the degree of benefits helpers provide (Kramer, 2015).

From these, we can see that in most cooperative breeding populations, helpers usually discriminate positively towards more closely related individuals, when providing help. Thus, it is easy to see, why others can choose to support an individual’s reproductive interest, provided the specific conditions enable the cost/benefit relation proposed by Hamilton.

Turning to the second question kin selection theory addresses, that is, whether helpers really make a difference in maternal fitness and the well-being of the offspring. It has been concluded that cooperative breeders, indeed, have a positive impact on the fitness of the mother and the survival, and health of the child (Kramer, 2010). Kramer also, referring to several studies, emphasized the importance of grandmothers and juveniles participating in breeding activities, whereas both classes of helpers increase the fertility of either their mothers or daughters, by increasing child survivorship and decreasing birth intervals. Furthermore, fathers participating in breeding have similar effects as grandmothers and juveniles, mainly by providing food to both the offspring and the mother.

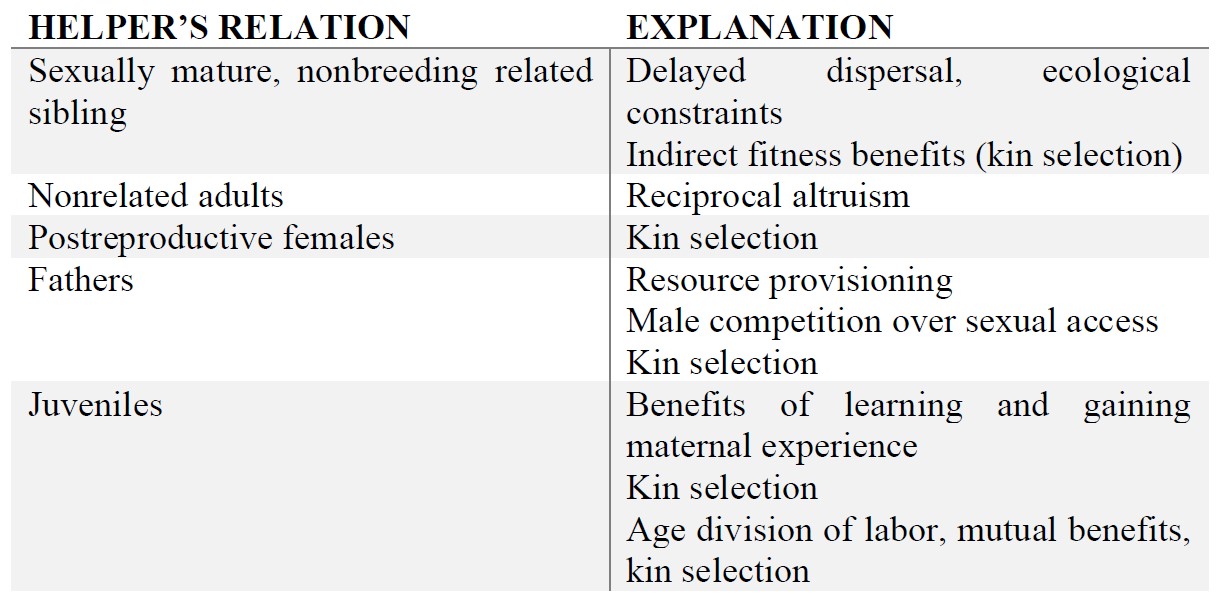

We can see now that kin-based positive discrimination in the case of providing allomaternal care is beneficent, in several respects, both for the mother and the offspring. This way, it is no mystery why sexually mature helpers engage in such costly behaviors while decreasing their own reproductive chances. The costs and benefits of helping involve various explanations, depending on the helper’s relatedness. These types of relatedness and their corresponding explanations are summarized in the following table (Kramer, 2015, 5. p.):

What we have already seen, is that kin-based positive discrimination has evolutionary benefits, with an overall higher payoff, given Hamilton’s formula. However, at this point, the question appeared to me, what is the case, where the coefficient of relatedness (r) is so low, that we would naturally predict selection against helping? This was the step, where I found myself thinking about different forms of altruism, and realized that kin selection theory only provides a good explanation for specific cases of helping, whereas other cooperative and beneficent behaviors cannot be accounted for only by rb > c.

Kramer also raised similar concerns: “cooperative behaviors may be motivated by factors besides kin selection. Researchers have raised the point that kin selection is an ultimate cause focused on fitness payoffs. Because these payoffs often are time delayed, kin selection may be insufficient to explain the motivation to cooperate.” (Kramer, 2015, 7. p.) My concerns about the feasibility of kin selection as an ultimate explanation of helping seems grounded, so now I will move on to examine, whether altruism could be a possible alternative accounting for different forms of cooperative behaviors with no relatedness present as a motivational factor for preferring helping.

Altruism and other types of cooperative and beneficent behaviors

First, I would like to examine what the term altruism refers to, in a biological or evolutionary context. The word, in general, is used as an antonym of egoism, from this starting point, we could define altruism in a biological context, as performing an action that is at the cost to the individual performing it, but benefits another individual, either directly or indirectly. A somewhat more precise definition could be made by including some terms used in ethology or social evolution: altruism consists of such behavior, performed by an individual, that increases the fitness of some other individual, whereas decreases the fitness of the actor.

Some definitions of altruism deny the possibility of reciprocity, that is what we can consider as ideal altruism, but for my argument, I would like to examine another form of altruism. Besides kin selection, as a form of altruism where there is the factor of relatedness at play also, we can see a somewhat more refined evolutionary mechanism not necessarily including relatedness: reciprocal altruism.

Reciprocal altruism in evolutionary biology refers to those behaviors, where an organism performs an action in such a manner that it increases the inclusive fitness of another organism, not closely related while reducing its own inclusive fitness, complemented with the expectation towards the organism receiving the benefit to perform a similar action in the future. Robert Trivers first coined the term in an essay published in 1971: The Evolution of Reciprocal Altruism. In the following section, I briefly summarize his article’s main arguments.

Trivers’s conception of reciprocal altruism

The main intention of Trivers’s article is to give a reasonable model accounting for the natural selection towards reciprocally altruistic behavior. His concerns towards Hamilton’s kin selection theory have the same basis as mine: ‘degree of relationship is an important parameter in predicting how selection will operate, and behavior which appears altruistic may, on knowledge of the genetic relationships of the organisms involved, be explicable in terms of natural selection: those genes being selected for that contribute to their own perpetuation, regardless of which individual genes appear in.’ (Trivers, 1971, 35. p.) Trivers argues, that his model is applicable to cases of asymmetric beneficial transactions affecting organisms' inclusive fitness, where the parties are even members of different species while ruling out kin selections exclusivity by presenting how altruistic behaviors can be selected for.

He begins by introducing an analogy of a human saving another human’s life, by rescuing them from drowning. There is a specific set up for the constellation of cost/benefit ratios and probabilities, but the two main features of this analogy are: (1) there is an asymmetric relation between the cost/benefit ratio of the two parties, and (2) we have to assume a capacity to discriminate between ‘cheaters’ (those who would not reciprocate in the future) and ‘non-cheaters’.

In the first case, what can be said is that the benefits of reciprocity depend on the unequal distribution of the altruistic act’s cost/benefit ratio. This means that the costs paid by the helper are always lower than the benefit received. Complementing this principle, it is easily imaginable that in the case of a reversed scenario, the one who has already helped has the rightful expectation towards the other to pay the same amount of cost in order to gain the higher benefits. By not complying with this principle, if the one who has already been helped, this time not providing help will be labeled as a ‘cheater’ of the principle of reciprocity. Natural selection will select against cheaters if the future disadvantageous effects of cheating outweigh the advantages of not reciprocating. A clear case of this scenario would be if the first donor of an altruistic act would avoid donating any further altruistic gestures to the cheater. When the benefits of such lost possible transactions are greater than the costs of reciprocating, selection will act against the cheater, compared to those engaging in altruistic exchanges.

We can project these conditions to a bigger population, to generalize the argument. Suppose there are altruists and non-altruists in a population, where altruists will always favor being altruistic when the benefits of the recipient are significantly higher than the cost to the altruist. Here cost meaning the “degree to which the behavior retards the reproduction of the genes of the altruist”, whereas benefit meaning the “degree to which the behavior increases the rate of reproduction of the genes of the recipient.” (Trivers, 1971, 36. p.) Now we can assume that allele a2 is responsible for favoring altruistic behavior, while its alternative, a1, is responsible for avoiding altruistic behavior. Trivers distinguishes the following three possibilities:

- altruism spreads randomly throughout the population,

- altruism spreads non-randomly, based on kin selection of the recipients,

- altruism spreads non-randomly, based on the altruistic tendencies of the recipients.

In the first case, altruism spreading randomly, thus being irrespective of the future benefits a reciprocal relationship could have, allele a1 will replace allele a2, in a large population. In the second case, which has been analyzed extensively by Hamilton (1964), allele a2 will replace a1, given that the tendency is great enough for altruism to spread selectively to close kin. In this case, it is assumed necessary for altruists to have a capacity to discriminate between those having allele a1 or a2. However, this case holds the possibility of parasitism to occur, as the discriminatory capacity does not necessarily involve the capacity to differentiate between actually being close kin to altruists or just acting in such a way to receive the benefits of others' altruistic acts. In the third case, allele a2 will be favorably selected for, given that the net benefit of altruists is greater than that of non-altruists, while holding the net benefit is relatively small, which also decreases the net costs. This scenario will occur, if altruists negatively discriminate towards non-altruists, by diminishing the further possibility of altruistic acts towards the non-altruists.

Given the above-described selective tendencies, Trivers (1971) concludes that altruistic alleles would be favored insomuch as the net average benefit to altruists are greater than the average benefit of non-altruist. This is true in cases where altruists limit their altruistic acts to their fellow altruists. Therefore, compared to Hamilton’s (1964) formulation, this argument will also hold for altruistic acts transferred between individuals of different species.

Biological parameters of reciprocal altruism

Trivers (1971) moves on to state the three conditions for the greatest probability to favor altruistic behavior:

- given there are numerous altruistic situations throughout the lifetime of the altruists,

- an altruist in question frequently interacts with the same small group of individuals,

- pairs of altruists encounter altruistic situations in such a way that each of them is able to gain similar benefits at similar costs to each other.

From these three conditions, we can infer the following biological parameters, influencing the probability of selection towards reciprocally altruistic behavior.

- Life expectancy. The longer the lifetime of two random individuals, the greater the chance of engaging in many altruistic situations.

- Rate of dispersal. The lower the rate of individuals’ dispersal, the higher the chance of an individual interacting frequently with the same group of neighbors.

- The extent of mutual dependence. The dependence of individuals of a species on each other will promote to keep them living near to each other, therefore increasing the probability of encountering altruistic situations. Given the benefit of mutual dependence is greater when just a small group of members are together, it will increase the probability of the same set of individuals engaging in repeated interactions.

- Parental care. This is an extraordinary case for mutual dependence, as generally, in species presenting tendencies for parental care, the relationship of the juvenile and parent is asymmetrical to such extent, that there is usually no or relatively low chance of situations where the offspring can reciprocate its parents' altruism or perform an altruistic act for another offspring. However, this is only partly true, given the case of an uncommonly long period of parental care (e.g., in the case of primates).

- Dominance hierarchy. The hierarchical structure depending on dominance in a linear fashion entails an asymmetrical relationship between the dominant individuals and the dominated ones. Meaning that a given individual is dominant over another, but not the other way around. The strength of such dominance hierarchies can be a determinant factor of the chance altruistic situations can occur. Strong dominance hierarchies make it less probable, while weaker dominance hierarchies make it more probable for altruistic situations to occur.

- Aid in danger. Irrespective of the strength of dominance hierarchies present in a group, dominant individuals are usually receiving help from a less dominant individual, in threatening situations. These situations are rather exceptional, where variously dominant individuals engage in relatively symmetrical relations.

Trivers (1971) considers this list as a suggestion of some examples for the conditions positively influencing the evolution of reciprocal altruism.

Prisoner’s Dilemma as an analogy of symmetrical reciprocity

After describing the biological features contributing to the evolution of reciprocal altruism, Trivers (1971) turns to argue that reciprocal situations between two individuals, where the cost/benefit ratios are symmetrical, are similar to the scenario described by the Prisoner’s Dilemma, developed by game theorists.

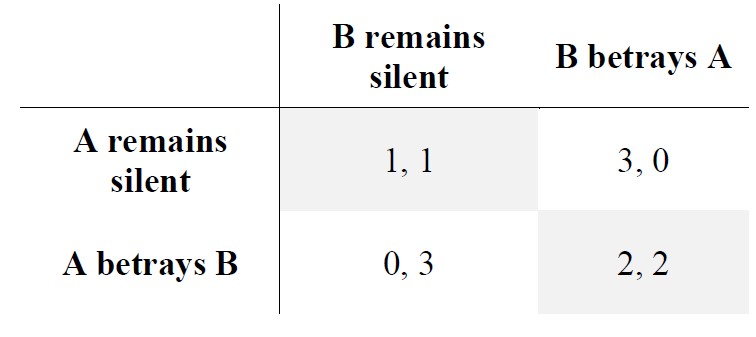

Game Theory is aimed at studying the mathematical models of strategic and rational decision-making. The Prisoner’s Dilemma is one of the numerous situations developed by scientists, having a specific reward-punishment constellation for either behaving cooperatively or non-cooperatively. The basic formulation of the Prisoner’s Dilemma between person A and B is the following:

A and B are arrested and detained. Both of them are separated and kept in solitary confinement, without any means of communicating with each other. There is not enough evidence to convict both A and B on the main charges, but there is enough to convict both on some smaller charges. The prosecutors make an offer for each prisoner, at the same time, to maintain the communication between them still impossible. Their options are either to cooperate with the authorities and betray the other or to cooperate with the other by staying silent. The possible four outcomes are the following:

- If A and B testify against each other, both of them have to serve two years in prison.

- If A betrays B, but B doesn’t make a confession against A, then A is released, and B is to serve three years.

- If B betrays A, but A doesn’t make a confession against B, then B is released, and A is to serve three years.

- If both of them remain silent, then each of them has to serve one year.

Using a table could better illustrate the payoff matrix of such decision’s outcomes, the numbers showing the years they would have to serve:

Here the altruistic choices are represented by remaining silent, and cheating by betrayal. The best case is when both A and B are altruistic, that is, remaining silent in spite of not being sure the other will do the same. However, this conception needs some refinement, if we wanted it to account for reciprocal altruism.

First, this situation can be made a bit more realistic by enabling the transaction to happen multiple times. Repetition allows for the capacity to detect cheaters to develop, by appealing to the memory of the participants. A, by remembering some previous betrayal from B, can change its strategies accordingly. This way, the condition of dealing with cheaters is met, so we are one step closer to explain reciprocal altruism, by setting up such a scenario where the overall benefits of both sides behaving altruistically is higher than any other option.

While it is clear that reciprocal altruism could only develop under highly specialized conditions, Trivers (1971) adds, that reciprocal altruism can be viewed as a situation depicted in the Prisoner’s Dilemma, given there is a time lag between the reciprocal payoff after helping the other. Here he differentiates between direct and indirect reciprocity, by bringing some examples. For example, food-sharing between partners can be an acceptable form for direct reciprocity, by one sharing food on one occasion, then the other returning the favor in the future. For indirect reciprocal altruism, Trivers (1971) brings the example of alarm calls, where the first alarm call sets out a series of events leading, after a time lag, to the benefit of the caller. He supposes the condition of time lag as one of the crucial factors in the explanation of reciprocal altruism; however, in the following sections, I am going to try to analyze, first, whether the condition of time lag is really that crucial, and second, whether the Prisoner’s Dilemma is a realistic basis for explaining reciprocal altruism.

Confusion around what is reciprocal altruism

To achieve the goals set out at the end of the last section, I will use the arguments proposed by Rothstein and Pierotti (1988). They begin by criticizing the definition and examples used by Trivers (1971), as they are neither accurate enough to accept the difference between kin selection and reciprocal altruism nor are his examples pointing at the phenomena he tries to explain as reciprocal altruism. For this, they propose a new formulation for reciprocal altruism, so the difference between kin selection, or other types of cooperation, and reciprocal altruism is clearer. Then, they define four categories of cooperative/beneficent behavior, to avoid further confusion originating from using inaccurate definitions.

The difference between kin selection and reciprocal altruism

Rothstein and Pierotti propose the following definition for reciprocal altruism: “RA [reciprocal altruism] is beneficent behavior whose selective maintenance depends upon reciprocation at a future time by the aided individual although the beneficent individual may receive some indirect increment to its inclusive fitness as a result of its aid.” (Rothstein and Pierotti, 1988, 193. p.) Therefore, they arrive at the conclusion, that there are cases where reciprocal altruism works similar to kin selection, however by adding extra conditions to Hamilton’s formula, we can clearly see the difference.

Let’s assume that individual A provides some aid to B, resulting in B’s increase of inclusive fitness. Let BeB refer to the benefit received by B, and C the costs of providing aid. The indirect increment of A’s inclusive fitness is BeB - C. Consider the following cases:

- If BeB > C is true, there is no reciprocation needed. In this case, selection could work identically to kin selection. (Remembering Hamilton’s formula: rb > c.)

- If Beb < C is true, reciprocation is needed from B, in order to A receive a positive increment to its inclusive fitness. BeA representing the benefits gained by A from B, A’s overall payoff would be: BeB + BeA - C.

- Therefore, cases of (1)-kind represent kin selection, and reciprocal altruism would be selected for, given: BeB + BeA > C > BeB.

The difference of this formulation compared to Trivers' (1971) is that in cases explained by (3) there is no need for the benefits reciprocated in the future to be higher than the initial costs of providing aid. Rothstein and Pierotti (1988) consider this reformulation of Trivers (1971) less restrictive, so to be capable of explaining such cases of reciprocal relations where the individuals help unrelated others, even in cases where the costs are greater than future benefits. (Rothstein and Pierotti, 1988)

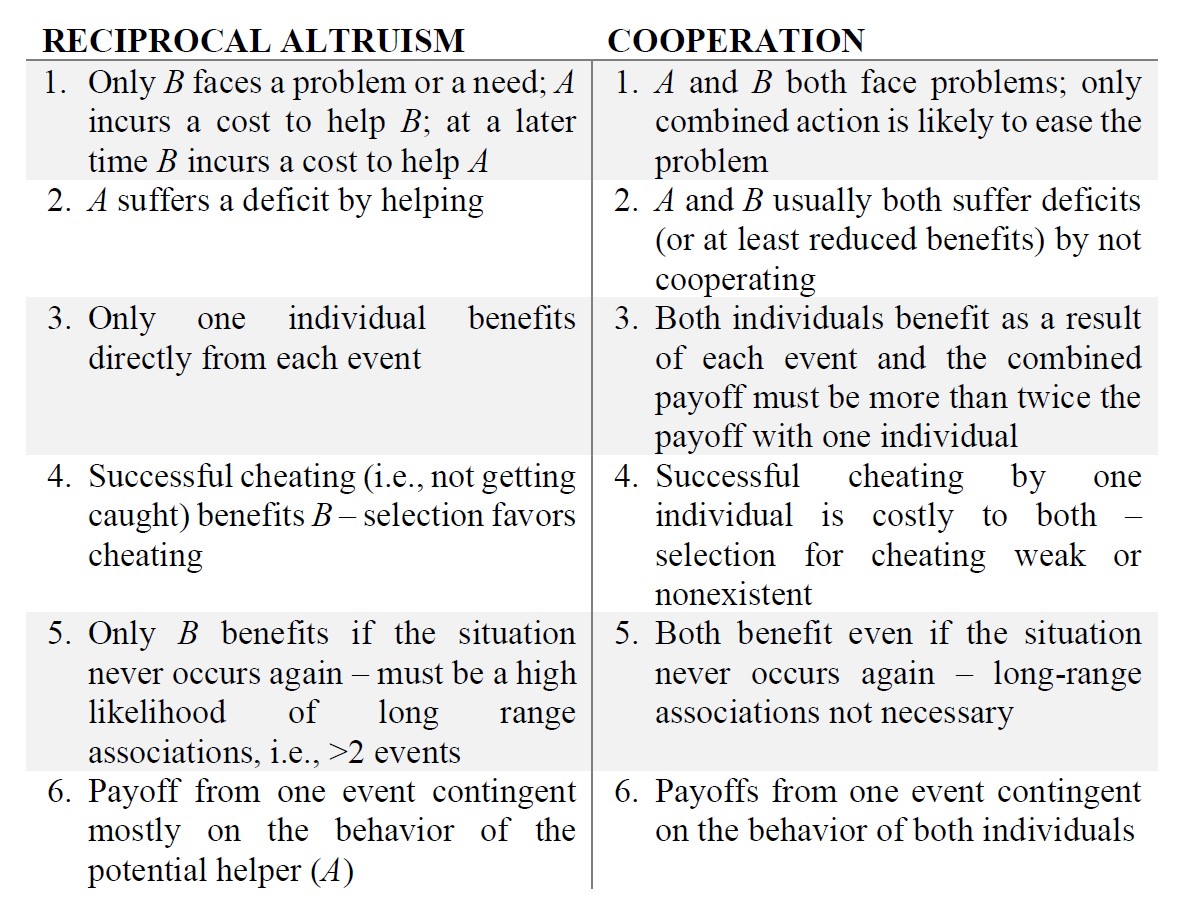

The difference between cooperation and reciprocal altruism

First, Rothstein and Pierotti (1988) turn to address the condition of time lag proposed by Trivers (1971). Only requiring a time lag between providing help and receiving some benefit misses the point of reciprocal altruism, because with this there is a chance to include phenomena in our definition that are other than reciprocal altruism. The crucial condition is rather that the original helper receives a future benefit because of a costly act by the initial recipient. They move on to show that, because of this mistaken overvaluation of the time lag condition, both of Trivers' (1971) examples of nonhuman reciprocal altruism represent some other phenomenon.

On the one hand, in the example of a bird’s alarm call, the assumed future indirect benefits of the caller don’t meet the requirement of reciprocity. That is, the indirect benefits received of the caller - if there are any - are not due to some costly behavior of the original recipient, but only accidental of that particular environmental setting, thus there is no reciprocity in such relation. Rothstein and Pierotti introduce the notion of by-product beneficence to refer to such situations.

On the other hand, Trivers' (1971) second example of a cleaner organism doesn’t meet the condition of the time lag while not providing a good determination of a costly act on the recipient. In this case, small fishes remove parasites of the larger host fish. However, Trivers (1971) mistakes the fact that the host doesn’t at the helper for receiving reciprocal benefits because of previous help. This causal relation is not clear, because a failure to carry out some behavior (that is, not eating the cleaner organism) does not mean a costly behavior on the part of the host. Therefore, this example rather shows a case of highly evolved mutualism than of reciprocal altruism, as the benefits received on each side are not due to a costly behavior of one or the other.

Another crucial feature of reciprocal altruism is the possibility of cheating. In order to consider some relation as reciprocally altruistic, we should assume the potential for cheating for real reciprocation. To differentiate between the cases that involve this potential and those that don’t, they introduce the conception of pseudoreciprocity, following Conner (1986). Pseudoreciprocity means that there are mutual benefits present in a relation, caused by the partaker’s behavior, but such behavior that is beneficent on both sides either way in each transaction, thus excluding the potential for cheating there is no real reciprocity.

Besides the ambiguity between reciprocal altruism and pseudoreciprocity, there is usually also confusion between cooperation and reciprocal altruism. Here the key difference lies in that cooperation involves simultaneous action on both sides to produce mutual benefits, while reciprocal altruism involves a rotating asymmetrical setup of helper and recipient with actions happening at different times. To clear up the supposed definitional problems, they present the following table, based on the dictionary definitions of ‘reciprocate’ and ‘cooperate’ (Rothstein and Pierotti, 1988, 198. p.):

Besides the difference in timing of actions in the two phenomena and the symmetries of the two situations, another difference worth emphasizing is selection’s “attitude” towards cheating. In the case of cooperation, there is no benefit of cheating as it would result in disadvantages due to not successfully realizing benefits. While in the case of reciprocal altruism, cheating provides a direct benefit for the original recipient of aid.

Another crucial difference is the number of events needed for each situation. In reciprocal altruism, there are at least 2 events needed to meet the conditions, whereas in cooperation involving simultaneous actions there is no reason to involve several events, as the benefits being mutual are the result of each individual’s work. In the following part of their article, Rothstein and Pierotti (1988) refer to cooperation as simultaneous cooperation, to avoid further confusion as reciprocal altruism can be viewed as a form of cooperation.

Four categories of cooperative and beneficent behavior

At this point, we can see now that what first has been defined as reciprocal altruism by Trivers (1971), was due to confusions emerging from inaccurate presentation of conditions by wrongly chosen examples. This approach resulted in mistaking other cooperative/beneficent behaviors to be cases of reciprocal altruism. Rothstein and Pierotti (1988) dissolved the confusion by introducing four categories of cooperative and beneficent behaviors. Here follow the steps involved in each of the categories presented (Rothstein and Pierotti, 1988, 201. p.):

- By-product beneficence:

- Only one individual donates services,

- Both individuals receive benefits,

- This is true for both the first and all following transactions,

- The asymmetry present in the relationship could be permanent,

- There is no selection for cheating, and no need for more than one act.

- Pseudoreciprocity:

- Only one individual donates services,

- But only the other receives benefits from the first act,

- Both benefit from the second act resulting from services by both, or only the original recipient,

- There is selection for cheating on the first act, but not on the second,

- Transactions must occur evenly (multiples of two).

- Reciprocal altruism:

- Only one individual donates services, and only the other receives benefits in the first and all following transactions,

- The donor/recipient asymmetry must reverse,

- Every act has to entail a high probability of future acts, (thus enabling the reversal of the asymmetry),

- There is selection for cheating on each occasion,

- Needs to be more than 2 acts, the further number of acts is unpredictable.

- Simultaneous cooperation:

- Both individuals donate services simultaneously,

- Both individuals receive benefits from all the transactions,

- There is weak selection for cheating, same on each act,

- No need for more than one act.

The authors conclude that while there is a possibility of intermediate cases of cooperative/beneficent behavior, their categorization can be applied to most, if not all, cases.

Conclusion and the arguments against the Prisoner’s Dilemma

However far it may seem, my main goal was to provide arguments against models based on the Prisoner’s Dilemma explaining altruism. But in order to achieve such a goal, first, I had to offer some insight into the necessary steps involved to make my thought process seem convincing.

The first problem of models based on the Prisoner’s Dilemma is neglecting the fact that in real-life cases of reciprocal altruism, both parties have knowledge about each other’s tendencies to help after the first couple of transactions, and their decision-making is not simultaneous as in the case of Prisoner’s Dilemma. The option to form decisions based on previous encounters is more restricted in situations like the Prisoner’s Dilemma, as the decision-making happens simultaneously, therefore these situations don’t involve asymmetric cost/benefit relations due to their simultaneity. Thus, the Prisoner’s Dilemma is rather similar to cases of simultaneous cooperation. However, this similarity is also too allowing, as the condition of not being able to communicate simply excludes the possibility of real cooperation. “Thus, the prisoner’s dilemma is a curious hybrid between RA [reciprocal altruism] and SCO [simultaneous cooperation] and is not the best way to model either phenomenon.”, Rothstein and Pierotti conclude (1988, 207. p.).

Another problem is over-emphasizing the role one particular strategy, namely the ‘tit-for-tat’ strategy, plays in models, based on the Prisoner’s Dilemma, intended to explain the initial evolution of reciprocal altruism. The strategy consists of repeating the previous action of the other individual: if A cheats first, and B cooperates, the next round A will cooperate and B will cheat, and so on. However, this strategy cannot represent reciprocal altruism, as there is the opportunity to mutually harm each other. Furthermore, ‘tit-for-tat’ is a rather complicated behavior, so it is highly improbable to emerge in a population without previous cooperative/beneficent behaviors present. Therefore, Rothstein and Pierotti propose, due to its simplicity, by-product beneficence to be a more accurate basis for the evolution of such complex cooperative/beneficent behaviors as reciprocal altruism.

As for making my argument’s scope a bit more general, and to reflect on the application of Game Theory as a means to develop models for evolutionary phenomena. We have to be overly careful when analyzing the situations we would like to model. As we have seen, the probability of failure to give proper examples and of defining phenomena without the dangers of risking confusion is high, and our inquiries have to take these risks into account, in order to avoid or lower them.

To conclude, we can see that in order to account for highly specialized evolutionary behaviors, there is a strong need for accurate model selection and explication of definitions, to avoid confusion and ambiguity between different, but strongly similar, phenomena. However, to achieve such a conclusion we cannot skip the necessary historical process of the natural debate revolving around conceptions.

Bibiliography

Hamilton, W.D. ‘The Genetical Evolution of Social Behaviour. I’. Journal of Theoretical Biology 7, no. 1 (July 1964): 1-16. [https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4].

Hamilton, W.D. ‘The Genetical Evolution of Social Behaviour. II’. Journal of Theoretical Biology 7, no. 1 (July 1964): 17-52. [https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4].

Kramer, Karen L. ‘Cooperative Breeding and Human Evolution’. In Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences, 1-13. American Cancer Society, 2015. [https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118900772.etrds0055].

Rothstein, Stephen I., and Raymond Pierotti. ‘Distinctions among Reciprocal Altruism, Kin Selection, and Cooperation and a Model for the Initial Evolution of Beneficent Behavior’. Ethology and Sociobiology 9, no. 2-4 (July 1988): 189-209. [https://doi.org/10.1016/0162-3095(88)90021-0].

Trivers, Robert L. ‘The Evolution of Reciprocal Altruism’. The Quarterly Review of Biology 46, no. 1 (1971): 35-57.